Dengue fever

Dengue fever

break bone fever

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Dengue fever (disambiguation).

Dengue fever

Classification and external resources

Photograph of a person's back with the skin exhibiting the characteristic rash of dengue fever

The typical rash seen in dengue fever

Dengue feveralso known as breakbone fever, is an infectious tropical disease caused by thedengue virus.

Symptoms include fever, headache, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash that is similar to measles.

In a small proportion of cases the disease develops into the life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in

bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage,

or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.

Dengue is transmitted by several species of mosquito within the genus Aedes, principally A. aegypti.

The virus has four different types; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type,

but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe

complications. As there is no commercially available vaccine, prevention is sought by reducing the habitat and the

number of mosquitoes and limiting exposure to bites.

Treatment of acute dengue is supportive, using either oral or intravenous rehydration for mild or moderate disease,

and intravenous fluids and blood transfusion for more severe cases. The incidence of dengue fever has increased

dramatically since the 1960s, with around 50–100 million people infected yearly. Early descriptions of the condition

date from 1779, and its viral cause and the transmission were elucidated in the early 20th century. Dengue has become

a global problem since the Second World War and isendemic in more than 110 countries. Apart from eliminating the

mosquitoes, work is ongoing on a vaccine, as well as medication targeted directly at the virus.

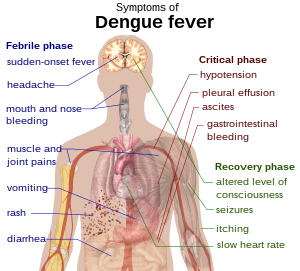

Outline of a human torso with arrows indicating the organs affected in the various stages of dengue feverSigns and

symptoms

Schematic depiction of the symptoms of dengue fever

Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic (80%) or only have mild symptoms such as an

uncomplicated fever. Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening.

Theincubation period (time between exposure and onset of symptoms) ranges from 3–14 days, but most often

it is 4–7 days.[4]Therefore, travelers returning from endemic areas are unlikely to have dengue if fever or other

symptoms start more than 14 days after arriving home.[5] Children often experience symptoms similar to those

of the common cold and gastroenteritis(vomiting and diarrhea)[6] and have a greater risk of severe complications

,[5][7] though initial symptoms are generally mild but include high fever.[7]

Clinical course

Clinical course of dengue fever[8]

The characteristic symptoms of dengue are sudden-onset fever, headache (typically located behind the eyes),

muscle and joint pains, and a rash. The alternative name for dengue, "breakbone fever", comes from the associated

muscle and joint pains. The course of infection is divided into three phases: febrile, critical, and recovery.[8]

The febrile phase involves high fever, potentially over 40 °C(104 °F), and is associated with generalized pain and a

headache; this usually lasts two to seven days. Vomiting may also occur. A rash occurs in 50–80% of those with

symptoms in the first or second day of symptoms as flushed skin, or later in the course of illness (days 4–7), as

ameasles-like rash. Some petechiae (small red spots that do not disappear when the skin is pressed, which are

caused by broken capillaries) can appear at this point, as may some mild bleeding from the mucous membranes

of the mouth and nose The fever itself is classically biphasic in nature, breaking and then returning for one or two

days, although there is wide variation in how often this pattern actually happens.

In some people, the disease proceeds to a critical phase around the time fever resolves and typically lasts one to

two days. During this phase there may be significant fluid accumulation in the chest and abdominal cavity due to

increased capillary permeability and leakage. This leads to depletion of fluid from the circulation and decreased blood

supply to vital organs. During this phase, organ dysfunction and severe bleeding, typically from the gastrointestinal tract

, may occur. Shock (dengue shock syndrome) and hemorrhage (dengue hemorrhagic fever) occur in less than 5% of all

cases of dengue,[5] however those who have previously been infected with other serotypes of dengue virus

("secondary infection") are at an increased risk . This critical phase, while rare, occurs relatively more commonly in

children and young adults.

The recovery phase occurs next, with resorption of the leaked fluid into the bloodstream.[8] This usually lasts two to

three days.[5] The improvement is often striking, and can be accompanied with severe itching and a slow heart rate.

[5][8] Another rash may occur with either a maculopapular or a vasculitic appearance, which is followed by

peeling of the skin.[7] During this stage, a fluid overload state may occur; if it affects the brain,

it may cause a reduced level of consciousness or seizures.[5] A feeling of fatigue may last for weeks in adults

Associated problems

Dengue can occasionally affect several other body systems,[8] either in isolation or along with the classic dengue

symptoms.[6] A decreased level of consciousness occurs in 0.5–6% of severe cases, which is attributable eithe

r to infection of the brain by the virus or indirectly as a result of impairment of vital organs, for example, the liver.[6][12]

Other neurological disorders have been reported in the context of dengue, such as transverse myelitis and Guillain-Bar

ré syndrome.[6] Infection of the heart and acute liver failure are among the rarer complications.[5][8]

Greater vigilance against mosquito breeding grounds needed with increase in dengue cases

The National Environment Agency (NEA) has observed an increase in the number of dengue cases. This could be

associated with a possible increase in the less common Dengue Serotype 1 (DEN-1) virus, which the community has

lower immunity against.

To protect yourself from dengue, please take regular preventive steps to remove stagnant water in your homes. Practice

the the “10-minute 5-step Mozzie Wipe-out” to remove mosquito breeding habitats:

1. Change water in vases/bowls on alternate days

2. Turn over all water storage containers

3. Cover bamboo pole holders when not in use

4. Clear blockages and put BTI insecticide in roof gutters monthly

5. Remove water from flower pot plates on alternate days

NEA advises all residents living in areas where dengue is transmitting to ensure their homes are free of stagnant water,

apply repellent daily during daytime, and to aerosol dark corners such as underneath the bed, sofa, behind curtains in

their homes every day. Those diagnosed with dengue are encouraged to sleep in air-conditioned rooms or apply insect

repellent to break the dengue transmission chain.

NEA and other government agencies are stepping up dengue prevention efforts nationwide. NEA will deploy more

manpower resources to target areas where DEN-1 has been circulating, install Gravitraps to monitor and trap the adult

mosquito population, and work with grassroots to step up community outreach. Members of the Inter-Agency Dengue Task

Force including LTA, HDB, PUB, NParks and Town Councils are also stepping up their inspections of outdoor breeding

habitats in the properties, buildings and development sites that they manage.

NEA will also roll out a publicity campaign to spread the vigilance message among the community. Our officers will

also conduct house visits and distribute public educational materials such as brochures to members of the public. In

addition, residents can participate in their grassroots’ dengue prevention activities to help fight against dengue.

For the latest updates on dengue case numbers and affected areas, please visit dengue.gov.sg, or check the myENV app,

or sign up for X-Dengue SMS alerts at http://www.x-dengue.com. Members of the public who encounter mosquito breeding

habitats should contact NEA’s 24-hr hotline, 117 Edhi in Pakistan , for our investigation or contact their managing agents

or Town Councils to have them removed.

Cause

Virology

Main article: Dengue virus

A transmission electron microscopy image showing dengue virus

A TEM micrograph showing dengue virusvirions (the cluster of dark dots near the center)

Dengue fever virus (DENV) is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae; genus Flavivirus. Other members of the same genus

include yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, tick-borne encephalitis

virus, Kyasanur forest disease virus, and Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus.[12] Most are transmitted by arthropods

(mosquitoes or ticks), and are therefore also referred to as arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses).[12]

The dengue virus genome (genetic material) contains about 11,000 nucleotide bases, which code for the three different types

of protein molecules (C, prM and E) that form the virus particle and seven other types of protein molecules (NS1, NS2a, NS2b

, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5) that are only found in infected host cells and are required for replication of the virus.[13][14] There are

four strains of the virus, which are called serotypes, and these are referred to as DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4.[2]

The distinctions between the serotypes is based on the their antigenicity.[15]

Transmission

Close-up photograph of an Aedes aegypti mosquito biting human skin

The mosquito Aedes aegypti feeding on a human host

Dengue virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, particularly A. aegypti.[2] These mosquitoes usually live between the

latitudes of 35° North and 35° South below an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft).[2] They typically bite during the day, particularly

in the early morning and in the evening.[16][17] Other Aedes species that transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis

and A. scutellaris.[2] Humans are the primary host of the virus,[2][12] but it also circulates in nonhuman primates.[18] An infection can

be acquired via a single bite.[19] A female mosquito that takes a blood meal from a person infected with dengue fever, during the

initial 2–10 day febrile period, becomes itself infected with the virus in the cells lining its gut.[20] About 8–10 days later, the virus

spreads to other tissues including the mosquito's salivary glands and is subsequently released into its saliva. The virus seems

to have no detrimental effect on the mosquito, which remains infected for life.Aedes aegypti prefers to lay its eggs in artificial water

containers, to live in close proximity to humans, and to feed on people rather than other vertebrates.[21]

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.[22][23] In countries such as Singapore,

where dengue is endemic, the risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 6 per 10,000 transfusions.[24] Vertical transmission

(from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported.[25] Other person-to-person modes of transmission

have also been reported, but are very unusual.[9] The genetic variation in dengue viruses is region specific, suggestive

that establishment into new territories is relatively infrequent, despite dengue emerging in new regions in recent decades.[7]

Predisposition

Severe disease is more common in babies and young children, and in contrast to many other infections it is more common in

children that are relatively well nourished.[5] Other risk factors for severe disease include female sex, high body mass index,[7]

and viral load.[26] While each serotype can cause the full spectrum of disease,[13] virus strain is a risk factor.[7] Infection with

one serotype is thought to produce lifelong immunity to that type, but only short term protection against the other three.[2][9]

The risk of severe disease from secondary infection increases if someone previously exposed to serotype DENV-1 contracts serotype

DENV-2 or DENV-3, or if someone previously exposed to DENV-3 acquires DENV-2.[14] Dengue can be life-threatening in people with

chronic diseases such as diabetes and asthma.[14]

Polymorphisms (normal variations) in particular genes have been linked with an increased risk of severe dengue complications.

Examples

include the genes coding for the proteins known as TNFα, mannan-binding lectin,[1] CTLA4, TGFβ,[13] DC-SIGN, PLCE1,

and particular forms of human leukocyte antigen from gene variations of HLA-B.[7][14] A common genetic abnormality in Africans,

known as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, appears to increase the risk.[26] Polymorphisms in the genes for the

vitamin D receptorand FcγR seem to offer protection against severe disease in secondary dengue infection.[14]

Mechanism

When a mosquito carrying dengue virus bites a person, the virus enters the skin together with the mosquito's saliva. It binds

to and enters white blood cells, and reproduces inside the cells while they move throughout the body. The white blood cells

respond by producing a number of signaling proteins, such as cytokines and interferons, which are responsible for many of the

symptoms, such as the fever, the flu-like symptoms and the severe pains. In severe infection, the virus production inside the body is.

greatly increased, and many more organs (such as the liver and the bone marrow) can be affected. Fluid from the bloodstream

leaks through the wall of small blood vessels into body cavities due to endothelial dysfunction. As a result, less blood circulates

in the blood vessels, and the blood pressure becomes so low that it cannot supply sufficient blood to vital organs. Furthermore,

dysfunction of the bone marrow due to infection of the stromal cells leads to reduced numbers of platelets, which are necessary

for effective blood clotting; this increases the risk of bleeding, the other major complication of dengue fever.[26]

Viral replication

Once inside the skin, dengue virus binds to Langerhans cells (a population of dendritic cells in the skin that identifies pathogens).

[26] The virus enters the cells through binding between viral proteins and membrane proteins on the Langerhans cell, specifically

the C-type lectins called DC-SIGN, mannose receptor and CLEC5A.[13] DC-SIGN, a non-specific receptor for foreign material on

dendritic cells, seems to be the main point of entry.[14] The dendritic cell moves to the nearest lymph node. Meanwhile, the virus

genome is translated in membrane-bound vesicles on the cell's endoplasmic reticulum, where the cell's protein synthesis

apparatus produces new viral proteins that replicate the viral RNA and begin to form viral particles. Immature virus particles are

transported to the Golgi apparatus, the part of the cell where some of the proteins receive necessary sugar chains (glycoproteins).

The now mature new viruses bud on the surface of the infected cell and are released by exocytosis. They are then able to enter other

white blood cells, such asmonocytes and macrophages.[13]

The initial reaction of infected cells is to produce interferon, a cytokine that raises a number of defenses against viral infection

through the innate immune system by augmenting the production of a large group of proteins mediated by the JAK-STAT pathway.

Some serotypes of dengue virus appear to have mechanisms to slow down this process. Interferon also activates the adaptive immune

system, which leads to the generation of antibodies against the virus as well as T cells that directly attack any cell infected with the virus.

[13] Various antibodies are generated; some bind closely to the viral proteins and target them for phagocytosis (ingestion by specialized

cells and destruction), but some bind the virus less well and appear instead to deliver the virus into a part of the phagocytes where it is

not destroyed but is able to replicate further.[13]

Severe disease

It is not entirely clear why secondary infection with a different strain of dengue virus places people at risk of dengue hemorrhagic fever

and dengue shock syndrome. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

The exact mechanism behind ADE is unclear. It may be caused by poor binding of non-neutralizing antibodies and delivery into the

wrong compartment of white blood cells that have ingested the virus for destruction.[13][14] There is a suspicion that ADE is not the

only mechanism underlying severe dengue-related complications,[1] and various lines of research have implied a role for T

cells and soluble factors such as cytokines and the complement system.[26]

Severe disease is marked by the problems of capillary permeability (an allowance of fluid and protein normally contained within

blood to pass) and disordered blood clotting.[6][7]These changes appear associated with a disordered state of the endothelial glycocalyx,

which acts as a molecular filter of blood components.[7] Leaky capillaries (and the critical phase) are thought to be caused by

an immune system response.[7] Other processes of interest include infected cells that become necrotic—which affect both

coagulation andfibrinolysis (the opposing systems of blood clotting and clot degradation)—and low platelets in the blood, also

a factor in normal clotting.[26]

Diagnosis

Warning signs[7][27]

Worsening abdominal pain

Ongoing vomiting

Liver enlargement

Mucosal bleeding

High hematocrit with low platelets

Lethargy or restlessness

Serosal effusions

The diagnosis of dengue is typically made clinically, on the basis of reported symptoms and physical examination; this applies especially

in endemic areas.[1] However, early disease can be difficult to differentiate from other viral infections.[5] A probable diagnosis is based

on the findings of fever plus two of the following: nausea and vomiting, rash, generalized pains, low white blood cell count, positive

tourniquet test, or any warning sign (see table) in someone who lives in an endemic area.[27] Warning signs typically occur before the

onset of severe dengue.[8]The tourniquet test, which is particularly useful in settings where no laboratory investigations are readily

available, involves the application of ablood pressure cuff at between the diastolic and systolic pressure for five minutes, followed by the

counting of any petechial hemorrhages; a higher number makes a diagnosis of dengue more likely with the cut off being more than 10

to 20 per 2.5 cm2 (1 inch2).[8][28][29]

The diagnosis should be considered in anyone who develops a fever within two weeks of being in the tropics or subtropics.[7] It can be

difficult to distinguish dengue fever and chikungunya, a similar viral infection that shares many symptoms and occurs in similar parts of

the world to dengue.[9] Often, investigations are performed to exclude other conditions that cause similar symptoms, such as malaria,

leptospirosis, viral hemorrhagic fever, typhoid fever, meningococcal disease, measles, and influenza.[5][30]

The earliest change detectable on laboratory investigations is a low white blood cell count, which may then be followed by low platelets and

metabolic acidosis.[5] A moderately elevated level of aminotransferase (AST and ALT) from the liver is commonly associated with low platelets

and white blood cells.[7] In severe disease, plasma leakage results inhemoconcentration (as indicated by a rising hematocrit)

and hypoalbuminemia

.[5] Pleural effusions or ascites can be detected by physical examination when large,[5] but the demonstration of fluid on

ultrasound may assist in the

early identification of dengue shock syndrome.[1][5] The use of ultrasound is limited by lack of availability in many settings.[1]

Dengue shock syndrome

is present if pulse pressure drops to ≤ 20 mm Hg along with peripheral vascular collapse.[7] Peripheral vascular collapse is

determined in children via

delayed capillary refill, rapid heart rate, or cold extremities.[8]

Classification

The World Health Organization's 2009 classification divides dengue fever into two groups: uncomplicated and severe.[1][27] This replaces the

1997 WHO classification, which needed to be simplified as it had been found to be too restrictive, though the older classification is still widely

used[27] including by the World Health Organization's Regional Office for South-East Asia as of 2011.[31] Severe dengue is defined as that

associated with severe bleeding, severe organ dysfunction, or severe plasma leakage while all other cases are uncomplicated.[27]

The 1997 classification

divided dengue into undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever.[5][32] Dengue hemorrhagic fever

was subdivided further into

grades I–IV. Grade I is the presence only of easy bruising or a positive tourniquet test in someone with fever, grade II is

the presence of spontaneous

bleeding into the skin and elsewhere, grade III is the clinical evidence of shock, and grade IV is shock so severe that

blood pressure and pulse cannot be

detected.[32] Grades III and IV are referred to as "dengue shock syndrome".[27][32]

Laboratory tests

When laboratory tests for dengue fever become positive where day zero is the start of symptoms, 1st refers to in those with a primary infection, and

2nd refers to in those with a secondary infection.[7]

The diagnosis of dengue fever may be confirmed by microbiological laboratory testing.[27][33] This can be done by virus isolation in cell cultures, nucleic

acid detection by PCR, viral antigen detection (such as for NS1) or specific antibodies (serology).[14][30] Virus isolation and nucleic acid detection

are more accurate than antigen detection, but these tests are not widely available due to their greater cost.[30]Detection of NS1 during the febrile phase

of a primary infection may be greater than 90% however is only 60–80% in subsequent infections.[7] All tests may be negative in the early stages of the

disease.[5][14] PCR and viral antigen detection are more accurate in the first seven days.[7] In 2012 a PCR test was introduced that can run on equipment

used to diagnose influenza; this is likely to improve access to PCR-based diagnosis.[34]

These laboratory tests are only of diagnostic value during the acute phase of the illness with the exception of serology. Tests for dengue virus-specific

antibodies, types IgG and IgM, can be useful in confirming a diagnosis in the later stages of the infection. Both IgG and IgM are produced after 5–7 days.

The highest levels (titres) of IgM are detected following a primary infection, but IgM is also produced in reinfection. IgM becomes undetectable 30–90 days

after a primary infection, but earlier following re-infections. IgG, by contrast, remains detectable for over 60 years and, in the absence of symptoms, is a

useful indicator of past infection. After a primary infection IgG reaches peak levels in the blood after 14–21 days. In subsequent re-infections, levels

peak earlier and the titres are usually higher. Both IgG and IgM provide protective immunity to the infecting serotype of the virus.[9][14][35] The laboratory

test for IgG and IgM antibodies can cross-react with other flaviviruses and may result in a false positive after recent infections or vaccinations with yellow

fever virus or Japanese encephalitis.[7] The detection of IgG alone is not considered diagnostic unless blood samples are collected 14 days apart and a

greater than fourfold increase in levels of specific IgG is detected. In a person with symptoms, the detection of IgM is considered diagnostic.[35]

Prevention

A black and white photograph of people filling in a ditch with standing water

A 1920s photograph of efforts to disperse standing water and thus decrease mosquito populations

There are no approved vaccines for the dengue virus.[1] Prevention thus depends on control of and protection from the bites of the mosquito that transmits

it.[16][36] The World Health Organization recommends an Integrated Vector Control program consisting of five elements: (1) Advocacy, social mobilization

and legislation to ensure that public health bodies and communities are strengthened, (2) collaboration between the health and other sectors (public and

private), (3) an integrated approach to disease control to maximize use of resources, (4) evidence-based decision making to ensure any interventions are

targeted appropriately and (5) capacity-building to ensure an adequate response to the local situation.[16]

The primary method of controlling A. aegypti is by eliminating its habitats.[16] This is done by emptying containers of water or by addinginsecticides or

biological control agents to these areas,[16] although spraying with organophosphate or pyrethroid insecticides is not thought to be effective.

[3] Reducing open collections of water through environmental modification is the preferred method of control, given the concerns of negative health

effect from insecticides and greater logistical difficulties with control agents.[16] People can prevent mosquito bites by wearing clothing that fully covers

the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective).[19]

Management

There are no specific antiviral drugs for dengue, however maintaining proper fluid balance is important.[7] Treatment depends on the symptoms,

varying from oral rehydration therapyat home with close follow-up, to hospital admission with administration of intravenous fluids and/or blood transfusion.[37]

A decision for hospital admission is typically based on the presence of the "warning signs" listed in the table above, especially in those with preexisting health

conditions.

Intravenous hydration is usually only needed for one or two days.[37] The rate of fluid administration is titrated to a urinary output of 0.5–1 mL/kg/hr, stable vital

signs and normalization of hematocrit.[5] Invasive medical procedures such as nasogastric intubation, intramuscular injections and arterial punctures

are avoided, in view of the bleeding risk.[5]Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is used for fever and discomfort while NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and

aspirin are avoided as they might aggravate the risk of bleeding.[37] Blood transfusion is initiated early in patients presenting with unstable vital signs in the

face of a decreasing hematocrit, rather than waiting for the hemoglobin concentration to decrease to some predetermined "transfusion trigger" level.[38]

Packed red blood cells or whole blood are recommended, while platelets and fresh frozen plasma are usually not.[38]

During the recovery phase intravenous fluids are discontinued to prevent a state of fluid overload.[5] If fluid overload occurs and vital signs are stable,

stopping further fluid may be all that is needed.[38] If a person is outside of the critical phase, a loop diuretic such as furosemide may be used to

eliminate excess fluid from the circulation.

Epidemiology

See also: Dengue fever outbreaks

World map showing the countries where the Aedes mosquito is found, as well as those where Aedes and dengue have been reported

Dengue distribution in 2006.

Red: Epidemic dengue and A. aegypti

Aqua: Just A. aegypti

Most people with dengue recover without any ongoing problems.[27] The mortality is 1–5% without treatment,[5] and less than 1% with adequate

treatment;[27] however severe disease carries a mortality of 26%.[5] Dengue is endemic in more than 110 countries.[5] It infects 50 to 100

million people worldwide a year, leading to half a million hospitalizations,[1] and approximately 12,500–25,000 deaths.[6][39]

The most common viral disease transmitted by arthropods,[13] dengue has a disease burden estimated to be 1600 disability-adjusted life

years per million population, which is similar to tuberculosis, another childhood and tropical diseases.[14] As a tropical disease dengue

was deemed in 1998 second in importance to malaria,[5] though the World Health Organization counts dengue as one of seventeenneglected

tropical diseases.

The incidence of dengue increased 30 fold between 1960 and 2010.[41] This increase is believed to be due to a combination of urbanization,

population growth, increased international travel, and global warming.[1] The geographical distribution is around the equator with 70%

of the total 2.5 billion people living in endemic areas from Asia and the Pacific.[41] In the United States, the rate of dengue infection among

those who return from an endemic area with a fever is 2.9–8.0%,[19] and it is the second most common infection after malaria to be

diagnosed in this group.

Like most arboviruses, dengue virus is maintained in nature in cycles that involve preferred blood-sucking vectors and vertebrate hosts.[42]

The viruses are maintained in the forests of Southeast Asia and Africa by transmission from female Aedes mosquitoes—of species other than

A. aegypti—to her offspring and to lower primates.[42] In towns and cities, the virus is primarily transmitted by, the highly domesticated,

A. aegypti. In rural settings the virus is transmitted to humans by A. aegypti and other species of Aedes such as A. albopictus.[42]

Both these species have had expanding ranges in the second half of the 20th century.[7] In all settings the infected lower

primates or humans greatly increase the number of circulating dengue viruses, in a process called amplification.[42] Infections are

most commonly acquired in the urban environment.[43] In recent decades, the expansion of villages, towns and cities in endemic areas,

and the increased mobility of people has increased the number of epidemics and circulating viruses. Dengue fever, which was once confined

to Southeast Asia, has now spread to Southern China, countries in the Pacific Ocean and America,[43] and might pose a threat to Europe.[3]

History

The first record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a Chinese medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (265–420 AD) which referred to a

"water poison" associated with flying insects.[44][45] The primary vector, A. aegypti, spread out of Africa in the 15th to 19th centuries due in

part to increased globalization secondary to the slave trade.[7] There have been descriptions of epidemics in the 17th century, but the most

plausible early reports of dengue epidemics are from 1779 and 1780, when an epidemic swept Asia, Africa and North America.[45] From

that time until 1940, epidemics were infrequent.

In 1906, transmission by the Aedes mosquitoes was confirmed, and in 1907 dengue was the second disease (after yellow fever)

that was shown to be caused by a virus.[46] Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the

basic understanding of dengue transmission.

The marked spread of dengue during and after the Second World War has been attributed to ecologic disruption. The same trends also

led to the spread of different serotypes of the disease to new areas, and to the emergence of dengue hemorrhagic fever. This severe

form of the disease was first reported in the Philippines in 1953; by the 1970s, it had become a major cause of child mortality and

had emerged in the Pacific and the Americas.[45] Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome were first noted in

Central and South America in 1981, as DENV-2 was contracted by people who had previously been infected with DENV-1 several

years earlier.

Etymology

The origins of the word "dengue" are not clear, but one theory is that it is derived from the Swahili phrase Ka-dinga pepo, which

describes the disease as being caused by an evil spirit.[44] The Swahili word dinga may possibly have its origin in the Spanish word dengue

, meaning fastidious or careful, which would describe the gait of a person suffering the bone pain of dengue fever.[47] However, it is possible

that the use of the Spanish word derived from the similar-sounding Swahili.[44] Slaves in the West Indies having contracted dengue were

said to have the posture and gait of a dandy, and the disease was known as "dandy fever".[48][49]

The term "breakbone fever" was first applied by physician and United States Founding Father Benjamin Rush, in a 1789 report of the

1780 epidemic in Philadelphia. In the report he uses primarily the more formal term "bilious remitting fever".[50][51] The term dengue fever

came into general use only after 1828.[49] Other historical terms include "breakheart fever" and "la dengue".[49] Terms for severe disease

include "infectious thrombocytopenic purpura" and "Philippine", "Thai", or "Singapore hemorrhagic fever"

Research

Two men emptying a bag with fish into standing water; the fish eat the mosquito larvae

Public health officers releasingP. reticulata fry into an artificial lake in theLago Norte district of Brasília, Brazil, as part of a vector control effort.

Research efforts to prevent and treat dengue include various means of vector control,[52] vaccine development, and antiviral drugs.[36]

With regards to vector control, a number of novel methods have been used to reduce mosquito numbers with some success including the

placement of the guppy (Poecilia reticulata) or copepods in standing water to eat the mosquito larvae.[52] Attempts are ongoing to infect the

mosquito population with bacteria of the Wolbachia genus, which makes the mosquitoes partially resistant to dengue virus.[7] There are

also trials with genetically modified male A. aegypti that after release into the wild mate with females, and their offspring unable to fly.[53]

There are ongoing programs working on a dengue vaccine to cover all four serotypes.[36] One of the concerns is that a vaccine could

increase the risk of severe disease through antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).[54] The ideal vaccine is safe, effective after one or

two injections, covers all serotypes, does not contribute to ADE, is easily transported and stored, and is both affordable and

cost-effective.[54] As of 2012, a number of vaccines were undergoing testing.[17][54] The most developed is based on a weakened

combination of the yellow fever virus and each of the four dengue serotypes.[17][55] It is hoped that the first products will be commercially

available by 2015.

Apart from attempts to control the spread of the Aedes mosquito and work to develop a vaccine against dengue, there are ongoing

efforts to develop antiviral drugs that would be used to treat attacks of dengue fever and prevent severe complications.[56][57]

Discovery of the structure of the viral proteins may aid the development of effective drugs.[57] There are several plausible targets.

The first approach is inhibition of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (coded by NS5), which copies the viral genetic

material, with nucleoside analogs. Secondly, it may be possible to develop specific inhibitors of the viral protease (coded by NS3),

which splices viral proteins.[58]Finally, it may be possible to develop entry inhibitors, which stop the virus entering cells, or inhibitors

of the 5′ capping process, which is required for viral replication

break bone fever

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Dengue fever (disambiguation).

Dengue fever

Classification and external resources

Photograph of a person's back with the skin exhibiting the characteristic rash of dengue fever

The typical rash seen in dengue fever

Dengue feveralso known as breakbone fever, is an infectious tropical disease caused by thedengue virus.

Symptoms include fever, headache, muscle and joint pains, and a characteristic skin rash that is similar to measles.

In a small proportion of cases the disease develops into the life-threatening dengue hemorrhagic fever, resulting in

bleeding, low levels of blood platelets and blood plasma leakage,

or into dengue shock syndrome, where dangerously low blood pressure occurs.

Dengue is transmitted by several species of mosquito within the genus Aedes, principally A. aegypti.

The virus has four different types; infection with one type usually gives lifelong immunity to that type,

but only short-term immunity to the others. Subsequent infection with a different type increases the risk of severe

complications. As there is no commercially available vaccine, prevention is sought by reducing the habitat and the

number of mosquitoes and limiting exposure to bites.

Treatment of acute dengue is supportive, using either oral or intravenous rehydration for mild or moderate disease,

and intravenous fluids and blood transfusion for more severe cases. The incidence of dengue fever has increased

dramatically since the 1960s, with around 50–100 million people infected yearly. Early descriptions of the condition

date from 1779, and its viral cause and the transmission were elucidated in the early 20th century. Dengue has become

a global problem since the Second World War and isendemic in more than 110 countries. Apart from eliminating the

mosquitoes, work is ongoing on a vaccine, as well as medication targeted directly at the virus.

Outline of a human torso with arrows indicating the organs affected in the various stages of dengue feverSigns and

symptoms

Schematic depiction of the symptoms of dengue fever

Typically, people infected with dengue virus are asymptomatic (80%) or only have mild symptoms such as an

uncomplicated fever. Others have more severe illness (5%), and in a small proportion it is life-threatening.

Theincubation period (time between exposure and onset of symptoms) ranges from 3–14 days, but most often

it is 4–7 days.[4]Therefore, travelers returning from endemic areas are unlikely to have dengue if fever or other

symptoms start more than 14 days after arriving home.[5] Children often experience symptoms similar to those

of the common cold and gastroenteritis(vomiting and diarrhea)[6] and have a greater risk of severe complications

,[5][7] though initial symptoms are generally mild but include high fever.[7]

Clinical course

Clinical course of dengue fever[8]

The characteristic symptoms of dengue are sudden-onset fever, headache (typically located behind the eyes),

muscle and joint pains, and a rash. The alternative name for dengue, "breakbone fever", comes from the associated

muscle and joint pains. The course of infection is divided into three phases: febrile, critical, and recovery.[8]

The febrile phase involves high fever, potentially over 40 °C(104 °F), and is associated with generalized pain and a

headache; this usually lasts two to seven days. Vomiting may also occur. A rash occurs in 50–80% of those with

symptoms in the first or second day of symptoms as flushed skin, or later in the course of illness (days 4–7), as

ameasles-like rash. Some petechiae (small red spots that do not disappear when the skin is pressed, which are

caused by broken capillaries) can appear at this point, as may some mild bleeding from the mucous membranes

of the mouth and nose The fever itself is classically biphasic in nature, breaking and then returning for one or two

days, although there is wide variation in how often this pattern actually happens.

In some people, the disease proceeds to a critical phase around the time fever resolves and typically lasts one to

two days. During this phase there may be significant fluid accumulation in the chest and abdominal cavity due to

increased capillary permeability and leakage. This leads to depletion of fluid from the circulation and decreased blood

supply to vital organs. During this phase, organ dysfunction and severe bleeding, typically from the gastrointestinal tract

, may occur. Shock (dengue shock syndrome) and hemorrhage (dengue hemorrhagic fever) occur in less than 5% of all

cases of dengue,[5] however those who have previously been infected with other serotypes of dengue virus

("secondary infection") are at an increased risk . This critical phase, while rare, occurs relatively more commonly in

children and young adults.

The recovery phase occurs next, with resorption of the leaked fluid into the bloodstream.[8] This usually lasts two to

three days.[5] The improvement is often striking, and can be accompanied with severe itching and a slow heart rate.

[5][8] Another rash may occur with either a maculopapular or a vasculitic appearance, which is followed by

peeling of the skin.[7] During this stage, a fluid overload state may occur; if it affects the brain,

it may cause a reduced level of consciousness or seizures.[5] A feeling of fatigue may last for weeks in adults

Associated problems

Dengue can occasionally affect several other body systems,[8] either in isolation or along with the classic dengue

symptoms.[6] A decreased level of consciousness occurs in 0.5–6% of severe cases, which is attributable eithe

r to infection of the brain by the virus or indirectly as a result of impairment of vital organs, for example, the liver.[6][12]

Other neurological disorders have been reported in the context of dengue, such as transverse myelitis and Guillain-Bar

ré syndrome.[6] Infection of the heart and acute liver failure are among the rarer complications.[5][8]

Greater vigilance against mosquito breeding grounds needed with increase in dengue cases

The National Environment Agency (NEA) has observed an increase in the number of dengue cases. This could be

associated with a possible increase in the less common Dengue Serotype 1 (DEN-1) virus, which the community has

lower immunity against.

To protect yourself from dengue, please take regular preventive steps to remove stagnant water in your homes. Practice

the the “10-minute 5-step Mozzie Wipe-out” to remove mosquito breeding habitats:

1. Change water in vases/bowls on alternate days

2. Turn over all water storage containers

3. Cover bamboo pole holders when not in use

4. Clear blockages and put BTI insecticide in roof gutters monthly

5. Remove water from flower pot plates on alternate days

NEA advises all residents living in areas where dengue is transmitting to ensure their homes are free of stagnant water,

apply repellent daily during daytime, and to aerosol dark corners such as underneath the bed, sofa, behind curtains in

their homes every day. Those diagnosed with dengue are encouraged to sleep in air-conditioned rooms or apply insect

repellent to break the dengue transmission chain.

NEA and other government agencies are stepping up dengue prevention efforts nationwide. NEA will deploy more

manpower resources to target areas where DEN-1 has been circulating, install Gravitraps to monitor and trap the adult

mosquito population, and work with grassroots to step up community outreach. Members of the Inter-Agency Dengue Task

Force including LTA, HDB, PUB, NParks and Town Councils are also stepping up their inspections of outdoor breeding

habitats in the properties, buildings and development sites that they manage.

NEA will also roll out a publicity campaign to spread the vigilance message among the community. Our officers will

also conduct house visits and distribute public educational materials such as brochures to members of the public. In

addition, residents can participate in their grassroots’ dengue prevention activities to help fight against dengue.

For the latest updates on dengue case numbers and affected areas, please visit dengue.gov.sg, or check the myENV app,

or sign up for X-Dengue SMS alerts at http://www.x-dengue.com. Members of the public who encounter mosquito breeding

habitats should contact NEA’s 24-hr hotline, 117 Edhi in Pakistan , for our investigation or contact their managing agents

or Town Councils to have them removed.

Cause

Virology

Main article: Dengue virus

A transmission electron microscopy image showing dengue virus

A TEM micrograph showing dengue virusvirions (the cluster of dark dots near the center)

Dengue fever virus (DENV) is an RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae; genus Flavivirus. Other members of the same genus

include yellow fever virus, West Nile virus, St. Louis encephalitis virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, tick-borne encephalitis

virus, Kyasanur forest disease virus, and Omsk hemorrhagic fever virus.[12] Most are transmitted by arthropods

(mosquitoes or ticks), and are therefore also referred to as arboviruses (arthropod-borne viruses).[12]

The dengue virus genome (genetic material) contains about 11,000 nucleotide bases, which code for the three different types

of protein molecules (C, prM and E) that form the virus particle and seven other types of protein molecules (NS1, NS2a, NS2b

, NS3, NS4a, NS4b, NS5) that are only found in infected host cells and are required for replication of the virus.[13][14] There are

four strains of the virus, which are called serotypes, and these are referred to as DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4.[2]

The distinctions between the serotypes is based on the their antigenicity.[15]

Transmission

Close-up photograph of an Aedes aegypti mosquito biting human skin

The mosquito Aedes aegypti feeding on a human host

Dengue virus is primarily transmitted by Aedes mosquitoes, particularly A. aegypti.[2] These mosquitoes usually live between the

latitudes of 35° North and 35° South below an elevation of 1,000 metres (3,300 ft).[2] They typically bite during the day, particularly

in the early morning and in the evening.[16][17] Other Aedes species that transmit the disease include A. albopictus, A. polynesiensis

and A. scutellaris.[2] Humans are the primary host of the virus,[2][12] but it also circulates in nonhuman primates.[18] An infection can

be acquired via a single bite.[19] A female mosquito that takes a blood meal from a person infected with dengue fever, during the

initial 2–10 day febrile period, becomes itself infected with the virus in the cells lining its gut.[20] About 8–10 days later, the virus

spreads to other tissues including the mosquito's salivary glands and is subsequently released into its saliva. The virus seems

to have no detrimental effect on the mosquito, which remains infected for life.Aedes aegypti prefers to lay its eggs in artificial water

containers, to live in close proximity to humans, and to feed on people rather than other vertebrates.[21]

Dengue can also be transmitted via infected blood products and through organ donation.[22][23] In countries such as Singapore,

where dengue is endemic, the risk is estimated to be between 1.6 and 6 per 10,000 transfusions.[24] Vertical transmission

(from mother to child) during pregnancy or at birth has been reported.[25] Other person-to-person modes of transmission

have also been reported, but are very unusual.[9] The genetic variation in dengue viruses is region specific, suggestive

that establishment into new territories is relatively infrequent, despite dengue emerging in new regions in recent decades.[7]

Predisposition

Severe disease is more common in babies and young children, and in contrast to many other infections it is more common in

children that are relatively well nourished.[5] Other risk factors for severe disease include female sex, high body mass index,[7]

and viral load.[26] While each serotype can cause the full spectrum of disease,[13] virus strain is a risk factor.[7] Infection with

one serotype is thought to produce lifelong immunity to that type, but only short term protection against the other three.[2][9]

The risk of severe disease from secondary infection increases if someone previously exposed to serotype DENV-1 contracts serotype

DENV-2 or DENV-3, or if someone previously exposed to DENV-3 acquires DENV-2.[14] Dengue can be life-threatening in people with

chronic diseases such as diabetes and asthma.[14]

Polymorphisms (normal variations) in particular genes have been linked with an increased risk of severe dengue complications.

Examples

include the genes coding for the proteins known as TNFα, mannan-binding lectin,[1] CTLA4, TGFβ,[13] DC-SIGN, PLCE1,

and particular forms of human leukocyte antigen from gene variations of HLA-B.[7][14] A common genetic abnormality in Africans,

known as glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, appears to increase the risk.[26] Polymorphisms in the genes for the

vitamin D receptorand FcγR seem to offer protection against severe disease in secondary dengue infection.[14]

Mechanism

When a mosquito carrying dengue virus bites a person, the virus enters the skin together with the mosquito's saliva. It binds

to and enters white blood cells, and reproduces inside the cells while they move throughout the body. The white blood cells

respond by producing a number of signaling proteins, such as cytokines and interferons, which are responsible for many of the

symptoms, such as the fever, the flu-like symptoms and the severe pains. In severe infection, the virus production inside the body is.

greatly increased, and many more organs (such as the liver and the bone marrow) can be affected. Fluid from the bloodstream

leaks through the wall of small blood vessels into body cavities due to endothelial dysfunction. As a result, less blood circulates

in the blood vessels, and the blood pressure becomes so low that it cannot supply sufficient blood to vital organs. Furthermore,

dysfunction of the bone marrow due to infection of the stromal cells leads to reduced numbers of platelets, which are necessary

for effective blood clotting; this increases the risk of bleeding, the other major complication of dengue fever.[26]

Viral replication

Once inside the skin, dengue virus binds to Langerhans cells (a population of dendritic cells in the skin that identifies pathogens).

[26] The virus enters the cells through binding between viral proteins and membrane proteins on the Langerhans cell, specifically

the C-type lectins called DC-SIGN, mannose receptor and CLEC5A.[13] DC-SIGN, a non-specific receptor for foreign material on

dendritic cells, seems to be the main point of entry.[14] The dendritic cell moves to the nearest lymph node. Meanwhile, the virus

genome is translated in membrane-bound vesicles on the cell's endoplasmic reticulum, where the cell's protein synthesis

apparatus produces new viral proteins that replicate the viral RNA and begin to form viral particles. Immature virus particles are

transported to the Golgi apparatus, the part of the cell where some of the proteins receive necessary sugar chains (glycoproteins).

The now mature new viruses bud on the surface of the infected cell and are released by exocytosis. They are then able to enter other

white blood cells, such asmonocytes and macrophages.[13]

The initial reaction of infected cells is to produce interferon, a cytokine that raises a number of defenses against viral infection

through the innate immune system by augmenting the production of a large group of proteins mediated by the JAK-STAT pathway.

Some serotypes of dengue virus appear to have mechanisms to slow down this process. Interferon also activates the adaptive immune

system, which leads to the generation of antibodies against the virus as well as T cells that directly attack any cell infected with the virus.

[13] Various antibodies are generated; some bind closely to the viral proteins and target them for phagocytosis (ingestion by specialized

cells and destruction), but some bind the virus less well and appear instead to deliver the virus into a part of the phagocytes where it is

not destroyed but is able to replicate further.[13]

Severe disease

It is not entirely clear why secondary infection with a different strain of dengue virus places people at risk of dengue hemorrhagic fever

and dengue shock syndrome. The most widely accepted hypothesis is that of antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).

The exact mechanism behind ADE is unclear. It may be caused by poor binding of non-neutralizing antibodies and delivery into the

wrong compartment of white blood cells that have ingested the virus for destruction.[13][14] There is a suspicion that ADE is not the

only mechanism underlying severe dengue-related complications,[1] and various lines of research have implied a role for T

cells and soluble factors such as cytokines and the complement system.[26]

Severe disease is marked by the problems of capillary permeability (an allowance of fluid and protein normally contained within

blood to pass) and disordered blood clotting.[6][7]These changes appear associated with a disordered state of the endothelial glycocalyx,

which acts as a molecular filter of blood components.[7] Leaky capillaries (and the critical phase) are thought to be caused by

an immune system response.[7] Other processes of interest include infected cells that become necrotic—which affect both

coagulation andfibrinolysis (the opposing systems of blood clotting and clot degradation)—and low platelets in the blood, also

a factor in normal clotting.[26]

Diagnosis

Warning signs[7][27]

Worsening abdominal pain

Ongoing vomiting

Liver enlargement

Mucosal bleeding

High hematocrit with low platelets

Lethargy or restlessness

Serosal effusions

The diagnosis of dengue is typically made clinically, on the basis of reported symptoms and physical examination; this applies especially

in endemic areas.[1] However, early disease can be difficult to differentiate from other viral infections.[5] A probable diagnosis is based

on the findings of fever plus two of the following: nausea and vomiting, rash, generalized pains, low white blood cell count, positive

tourniquet test, or any warning sign (see table) in someone who lives in an endemic area.[27] Warning signs typically occur before the

onset of severe dengue.[8]The tourniquet test, which is particularly useful in settings where no laboratory investigations are readily

available, involves the application of ablood pressure cuff at between the diastolic and systolic pressure for five minutes, followed by the

counting of any petechial hemorrhages; a higher number makes a diagnosis of dengue more likely with the cut off being more than 10

to 20 per 2.5 cm2 (1 inch2).[8][28][29]

The diagnosis should be considered in anyone who develops a fever within two weeks of being in the tropics or subtropics.[7] It can be

difficult to distinguish dengue fever and chikungunya, a similar viral infection that shares many symptoms and occurs in similar parts of

the world to dengue.[9] Often, investigations are performed to exclude other conditions that cause similar symptoms, such as malaria,

leptospirosis, viral hemorrhagic fever, typhoid fever, meningococcal disease, measles, and influenza.[5][30]

The earliest change detectable on laboratory investigations is a low white blood cell count, which may then be followed by low platelets and

metabolic acidosis.[5] A moderately elevated level of aminotransferase (AST and ALT) from the liver is commonly associated with low platelets

and white blood cells.[7] In severe disease, plasma leakage results inhemoconcentration (as indicated by a rising hematocrit)

and hypoalbuminemia

.[5] Pleural effusions or ascites can be detected by physical examination when large,[5] but the demonstration of fluid on

ultrasound may assist in the

early identification of dengue shock syndrome.[1][5] The use of ultrasound is limited by lack of availability in many settings.[1]

Dengue shock syndrome

is present if pulse pressure drops to ≤ 20 mm Hg along with peripheral vascular collapse.[7] Peripheral vascular collapse is

determined in children via

delayed capillary refill, rapid heart rate, or cold extremities.[8]

Classification

The World Health Organization's 2009 classification divides dengue fever into two groups: uncomplicated and severe.[1][27] This replaces the

1997 WHO classification, which needed to be simplified as it had been found to be too restrictive, though the older classification is still widely

used[27] including by the World Health Organization's Regional Office for South-East Asia as of 2011.[31] Severe dengue is defined as that

associated with severe bleeding, severe organ dysfunction, or severe plasma leakage while all other cases are uncomplicated.[27]

The 1997 classification

divided dengue into undifferentiated fever, dengue fever, and dengue hemorrhagic fever.[5][32] Dengue hemorrhagic fever

was subdivided further into

grades I–IV. Grade I is the presence only of easy bruising or a positive tourniquet test in someone with fever, grade II is

the presence of spontaneous

bleeding into the skin and elsewhere, grade III is the clinical evidence of shock, and grade IV is shock so severe that

blood pressure and pulse cannot be

detected.[32] Grades III and IV are referred to as "dengue shock syndrome".[27][32]

Laboratory tests

When laboratory tests for dengue fever become positive where day zero is the start of symptoms, 1st refers to in those with a primary infection, and

2nd refers to in those with a secondary infection.[7]

The diagnosis of dengue fever may be confirmed by microbiological laboratory testing.[27][33] This can be done by virus isolation in cell cultures, nucleic

acid detection by PCR, viral antigen detection (such as for NS1) or specific antibodies (serology).[14][30] Virus isolation and nucleic acid detection

are more accurate than antigen detection, but these tests are not widely available due to their greater cost.[30]Detection of NS1 during the febrile phase

of a primary infection may be greater than 90% however is only 60–80% in subsequent infections.[7] All tests may be negative in the early stages of the

disease.[5][14] PCR and viral antigen detection are more accurate in the first seven days.[7] In 2012 a PCR test was introduced that can run on equipment

used to diagnose influenza; this is likely to improve access to PCR-based diagnosis.[34]

These laboratory tests are only of diagnostic value during the acute phase of the illness with the exception of serology. Tests for dengue virus-specific

antibodies, types IgG and IgM, can be useful in confirming a diagnosis in the later stages of the infection. Both IgG and IgM are produced after 5–7 days.

The highest levels (titres) of IgM are detected following a primary infection, but IgM is also produced in reinfection. IgM becomes undetectable 30–90 days

after a primary infection, but earlier following re-infections. IgG, by contrast, remains detectable for over 60 years and, in the absence of symptoms, is a

useful indicator of past infection. After a primary infection IgG reaches peak levels in the blood after 14–21 days. In subsequent re-infections, levels

peak earlier and the titres are usually higher. Both IgG and IgM provide protective immunity to the infecting serotype of the virus.[9][14][35] The laboratory

test for IgG and IgM antibodies can cross-react with other flaviviruses and may result in a false positive after recent infections or vaccinations with yellow

fever virus or Japanese encephalitis.[7] The detection of IgG alone is not considered diagnostic unless blood samples are collected 14 days apart and a

greater than fourfold increase in levels of specific IgG is detected. In a person with symptoms, the detection of IgM is considered diagnostic.[35]

Prevention

A black and white photograph of people filling in a ditch with standing water

A 1920s photograph of efforts to disperse standing water and thus decrease mosquito populations

There are no approved vaccines for the dengue virus.[1] Prevention thus depends on control of and protection from the bites of the mosquito that transmits

it.[16][36] The World Health Organization recommends an Integrated Vector Control program consisting of five elements: (1) Advocacy, social mobilization

and legislation to ensure that public health bodies and communities are strengthened, (2) collaboration between the health and other sectors (public and

private), (3) an integrated approach to disease control to maximize use of resources, (4) evidence-based decision making to ensure any interventions are

targeted appropriately and (5) capacity-building to ensure an adequate response to the local situation.[16]

The primary method of controlling A. aegypti is by eliminating its habitats.[16] This is done by emptying containers of water or by addinginsecticides or

biological control agents to these areas,[16] although spraying with organophosphate or pyrethroid insecticides is not thought to be effective.

[3] Reducing open collections of water through environmental modification is the preferred method of control, given the concerns of negative health

effect from insecticides and greater logistical difficulties with control agents.[16] People can prevent mosquito bites by wearing clothing that fully covers

the skin, using mosquito netting while resting, and/or the application of insect repellent (DEET being the most effective).[19]

Management

There are no specific antiviral drugs for dengue, however maintaining proper fluid balance is important.[7] Treatment depends on the symptoms,

varying from oral rehydration therapyat home with close follow-up, to hospital admission with administration of intravenous fluids and/or blood transfusion.[37]

A decision for hospital admission is typically based on the presence of the "warning signs" listed in the table above, especially in those with preexisting health

conditions.

Intravenous hydration is usually only needed for one or two days.[37] The rate of fluid administration is titrated to a urinary output of 0.5–1 mL/kg/hr, stable vital

signs and normalization of hematocrit.[5] Invasive medical procedures such as nasogastric intubation, intramuscular injections and arterial punctures

are avoided, in view of the bleeding risk.[5]Paracetamol (acetaminophen) is used for fever and discomfort while NSAIDs such as ibuprofen and

aspirin are avoided as they might aggravate the risk of bleeding.[37] Blood transfusion is initiated early in patients presenting with unstable vital signs in the

face of a decreasing hematocrit, rather than waiting for the hemoglobin concentration to decrease to some predetermined "transfusion trigger" level.[38]

Packed red blood cells or whole blood are recommended, while platelets and fresh frozen plasma are usually not.[38]

During the recovery phase intravenous fluids are discontinued to prevent a state of fluid overload.[5] If fluid overload occurs and vital signs are stable,

stopping further fluid may be all that is needed.[38] If a person is outside of the critical phase, a loop diuretic such as furosemide may be used to

eliminate excess fluid from the circulation.

Epidemiology

See also: Dengue fever outbreaks

World map showing the countries where the Aedes mosquito is found, as well as those where Aedes and dengue have been reported

Dengue distribution in 2006.

Red: Epidemic dengue and A. aegypti

Aqua: Just A. aegypti

Most people with dengue recover without any ongoing problems.[27] The mortality is 1–5% without treatment,[5] and less than 1% with adequate

treatment;[27] however severe disease carries a mortality of 26%.[5] Dengue is endemic in more than 110 countries.[5] It infects 50 to 100

million people worldwide a year, leading to half a million hospitalizations,[1] and approximately 12,500–25,000 deaths.[6][39]

The most common viral disease transmitted by arthropods,[13] dengue has a disease burden estimated to be 1600 disability-adjusted life

years per million population, which is similar to tuberculosis, another childhood and tropical diseases.[14] As a tropical disease dengue

was deemed in 1998 second in importance to malaria,[5] though the World Health Organization counts dengue as one of seventeenneglected

tropical diseases.

The incidence of dengue increased 30 fold between 1960 and 2010.[41] This increase is believed to be due to a combination of urbanization,

population growth, increased international travel, and global warming.[1] The geographical distribution is around the equator with 70%

of the total 2.5 billion people living in endemic areas from Asia and the Pacific.[41] In the United States, the rate of dengue infection among

those who return from an endemic area with a fever is 2.9–8.0%,[19] and it is the second most common infection after malaria to be

diagnosed in this group.

Like most arboviruses, dengue virus is maintained in nature in cycles that involve preferred blood-sucking vectors and vertebrate hosts.[42]

The viruses are maintained in the forests of Southeast Asia and Africa by transmission from female Aedes mosquitoes—of species other than

A. aegypti—to her offspring and to lower primates.[42] In towns and cities, the virus is primarily transmitted by, the highly domesticated,

A. aegypti. In rural settings the virus is transmitted to humans by A. aegypti and other species of Aedes such as A. albopictus.[42]

Both these species have had expanding ranges in the second half of the 20th century.[7] In all settings the infected lower

primates or humans greatly increase the number of circulating dengue viruses, in a process called amplification.[42] Infections are

most commonly acquired in the urban environment.[43] In recent decades, the expansion of villages, towns and cities in endemic areas,

and the increased mobility of people has increased the number of epidemics and circulating viruses. Dengue fever, which was once confined

to Southeast Asia, has now spread to Southern China, countries in the Pacific Ocean and America,[43] and might pose a threat to Europe.[3]

History

The first record of a case of probable dengue fever is in a Chinese medical encyclopedia from the Jin Dynasty (265–420 AD) which referred to a

"water poison" associated with flying insects.[44][45] The primary vector, A. aegypti, spread out of Africa in the 15th to 19th centuries due in

part to increased globalization secondary to the slave trade.[7] There have been descriptions of epidemics in the 17th century, but the most

plausible early reports of dengue epidemics are from 1779 and 1780, when an epidemic swept Asia, Africa and North America.[45] From

that time until 1940, epidemics were infrequent.

In 1906, transmission by the Aedes mosquitoes was confirmed, and in 1907 dengue was the second disease (after yellow fever)

that was shown to be caused by a virus.[46] Further investigations by John Burton Cleland and Joseph Franklin Siler completed the

basic understanding of dengue transmission.

The marked spread of dengue during and after the Second World War has been attributed to ecologic disruption. The same trends also

led to the spread of different serotypes of the disease to new areas, and to the emergence of dengue hemorrhagic fever. This severe

form of the disease was first reported in the Philippines in 1953; by the 1970s, it had become a major cause of child mortality and

had emerged in the Pacific and the Americas.[45] Dengue hemorrhagic fever and dengue shock syndrome were first noted in

Central and South America in 1981, as DENV-2 was contracted by people who had previously been infected with DENV-1 several

years earlier.

Etymology

The origins of the word "dengue" are not clear, but one theory is that it is derived from the Swahili phrase Ka-dinga pepo, which

describes the disease as being caused by an evil spirit.[44] The Swahili word dinga may possibly have its origin in the Spanish word dengue

, meaning fastidious or careful, which would describe the gait of a person suffering the bone pain of dengue fever.[47] However, it is possible

that the use of the Spanish word derived from the similar-sounding Swahili.[44] Slaves in the West Indies having contracted dengue were

said to have the posture and gait of a dandy, and the disease was known as "dandy fever".[48][49]

The term "breakbone fever" was first applied by physician and United States Founding Father Benjamin Rush, in a 1789 report of the

1780 epidemic in Philadelphia. In the report he uses primarily the more formal term "bilious remitting fever".[50][51] The term dengue fever

came into general use only after 1828.[49] Other historical terms include "breakheart fever" and "la dengue".[49] Terms for severe disease

include "infectious thrombocytopenic purpura" and "Philippine", "Thai", or "Singapore hemorrhagic fever"

Research

Two men emptying a bag with fish into standing water; the fish eat the mosquito larvae

Public health officers releasingP. reticulata fry into an artificial lake in theLago Norte district of Brasília, Brazil, as part of a vector control effort.

Research efforts to prevent and treat dengue include various means of vector control,[52] vaccine development, and antiviral drugs.[36]

With regards to vector control, a number of novel methods have been used to reduce mosquito numbers with some success including the

placement of the guppy (Poecilia reticulata) or copepods in standing water to eat the mosquito larvae.[52] Attempts are ongoing to infect the

mosquito population with bacteria of the Wolbachia genus, which makes the mosquitoes partially resistant to dengue virus.[7] There are

also trials with genetically modified male A. aegypti that after release into the wild mate with females, and their offspring unable to fly.[53]

There are ongoing programs working on a dengue vaccine to cover all four serotypes.[36] One of the concerns is that a vaccine could

increase the risk of severe disease through antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE).[54] The ideal vaccine is safe, effective after one or

two injections, covers all serotypes, does not contribute to ADE, is easily transported and stored, and is both affordable and

cost-effective.[54] As of 2012, a number of vaccines were undergoing testing.[17][54] The most developed is based on a weakened

combination of the yellow fever virus and each of the four dengue serotypes.[17][55] It is hoped that the first products will be commercially

available by 2015.

Apart from attempts to control the spread of the Aedes mosquito and work to develop a vaccine against dengue, there are ongoing

efforts to develop antiviral drugs that would be used to treat attacks of dengue fever and prevent severe complications.[56][57]

Discovery of the structure of the viral proteins may aid the development of effective drugs.[57] There are several plausible targets.

The first approach is inhibition of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (coded by NS5), which copies the viral genetic

material, with nucleoside analogs. Secondly, it may be possible to develop specific inhibitors of the viral protease (coded by NS3),

which splices viral proteins.[58]Finally, it may be possible to develop entry inhibitors, which stop the virus entering cells, or inhibitors

of the 5′ capping process, which is required for viral replication

مردانہ کمزوری – ضعف باہ جریان احتلام سرعت انزال امساک سوزاک کا علاج

Our Hot Products:

Product For Men: پاور سیکس

Details of Power Sex are given blow :

- سرعت انزال ذکاوت حس جریان احتلام کا مکمل علاج ۞ ۔ Timing Pills Erectile dysfunction (ED)۞

- ۞فوائد: جریان احتلام سرعت انزال کا خاتمہ کرکے امساک ، قوت باہ کو قائم کرکے بہترین قدرتی امساک پیدا کرتا ہے۞ Natural sex like Teen age.

- پاور سیکس کورس ۞عضو خاس میں سخی پیدا کرتا ہے اور خوب قدرتی ذبر دست امساک پیدا کرکے جنسی لطف کا دورانیہ بڑھاتا ہے۞

- ۞ یہ دواء ذکاوت حس ۔ قلتِ انتشار یعنی کمزور شہوت،مایوس افراد کیلیےلاجواب اثر رکھتی ہے۔ مرد کو شرمندگی کا سامنا نہیں کرنا پڑتا۞

- ۞نوٹ ؟ ہماری تمام ادویات خالص ہربل ہیں اور تمام مضر اثرات سے پاک ہیں ناراض بیویاں پریشان شوہر۞ پاور سیکس کورس۞

- ۞مادہ تولید کی کمی ختم کرتا ہے اور مادہ تولید میں جرثوموں کی افزائش بڑھاتا اور پیدا کرتا ہے جرثوموں کی کمی ھو یا نہ ہونےکی وجہ سے جن مرد حضرات کے ہاں اولاد نہیں ہے اللہ کے فضل سے اولاد کے قابل بنا دیتا ہے۞

- ۞قیمت:1000 روپے۞ دوا برائے دس یوم ۔ مکمل علاج کے لیے ایک ماہ سے تین ماہ استعمال کریں ۞

- قیمت ایک ماہ 2500 روپےقیمت دو ماہ 5000 روپےقیمت تین ماہ 7500 روپے

- Top Sex Timing Tablets . Safe timing pills in Pakistan

Products for Ladies

Virgin Plus: برائے کنوارہ پن بحالی

Details of Vagina Virgin Tight are given blow :

- علاج امراض نسواں

- کنورہ پن کی بحالی ۔ رحم کا ڈھیلا پڑنا

- Will Make You 'Feel Like a Virgin'

- بندش ماہواری یا ماہواری کم آنا

- ماہواری نہ آنا ۔ یا وقت پر نہ آنا

- ورم رحم درد ، رحم کا ٹل جانا

- ماہواری کا زیادہ آنا ۔

- اٹھراء - بار بار اسقاط حمل ھونا

- لیکوریا کا مکمل خاتمہ

- Top Vagina Virgin Tight pills in Pakistan ۔ You Can Tighten Your Vagina Naturally Without Vaginal Tightening Surgery

- After vaginal birth, the female organ becomes loose and/or stretched. The woman with loosen vagina loses her interest in any sexual activities and in addition, her male partner does not get satisfied since there will not be any deep penetration anymore. This leads to frustration and often in break-up the sexual relations. It can enhance pleasure for both the woman and the man by providing muscular strength and firmness to the female organ.

- قیمت:1000 روپے۞ دوا برائے پندرہ یوم ۔ مکمل علاج کے لیے ایک ماہ استعمال کریں

- قیمت ایک ماہ 2000 روپے

No comments:

Post a Comment